This is a guest post by Nancy Friedman, an AMN volunteer.

You’ve played Bach, Vivaldi, and Haydn for years on your modern instrument. But have you ever wished to play that music in historically-informed style … without investing in costly period instruments?

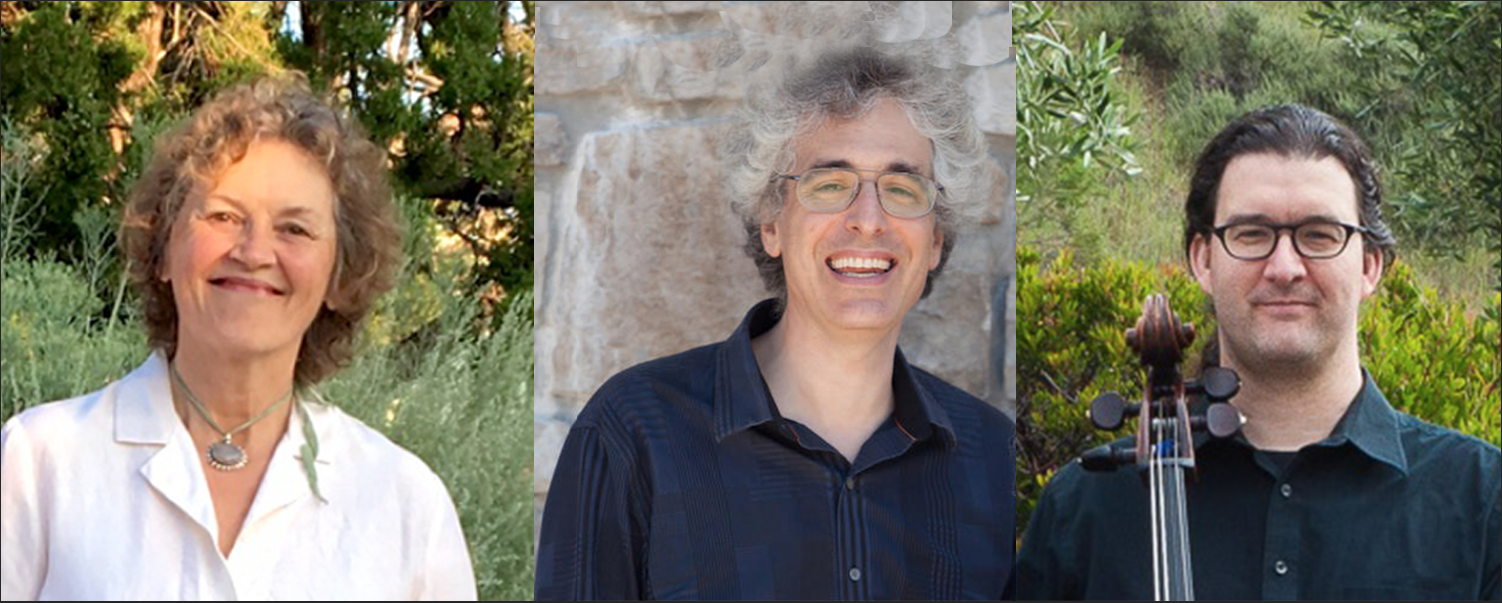

Now you can! Throughout October, Amateur Music Network is presenting Early Music for Modern Instruments, a series of online workshops for skilled amateur musicians taught by early-music mentors Elizabeth Blumenstock (violin), Eric Zivian (piano and fortepiano), and William Skeen (cello).

Elizabeth, Eric, and William

“With most of us still stuck at home, there’s never been a better time to expand our musical horizons,” says AMN founder and director Lolly Lewis. “If you’ve worked hard on the standard classical path, you know the repertoire. Now you can learn new tools and approaches from early-music specialists that will give you even more appreciation of the music you love.”

What makes early music different from modern music?

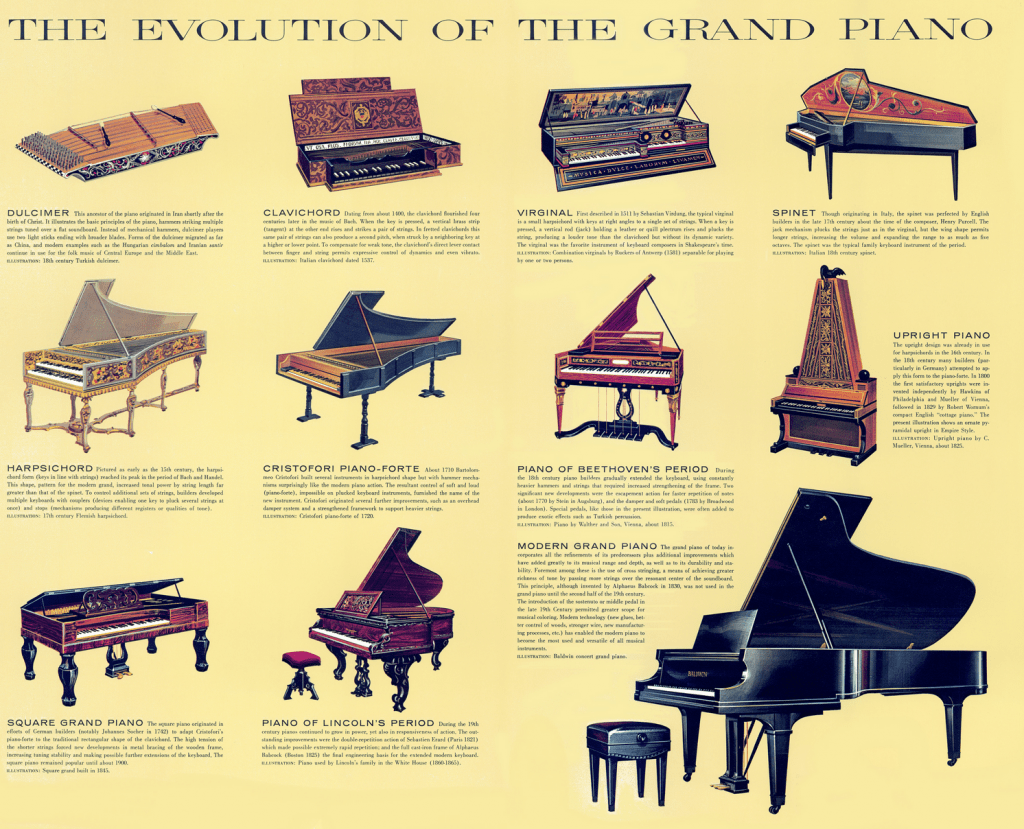

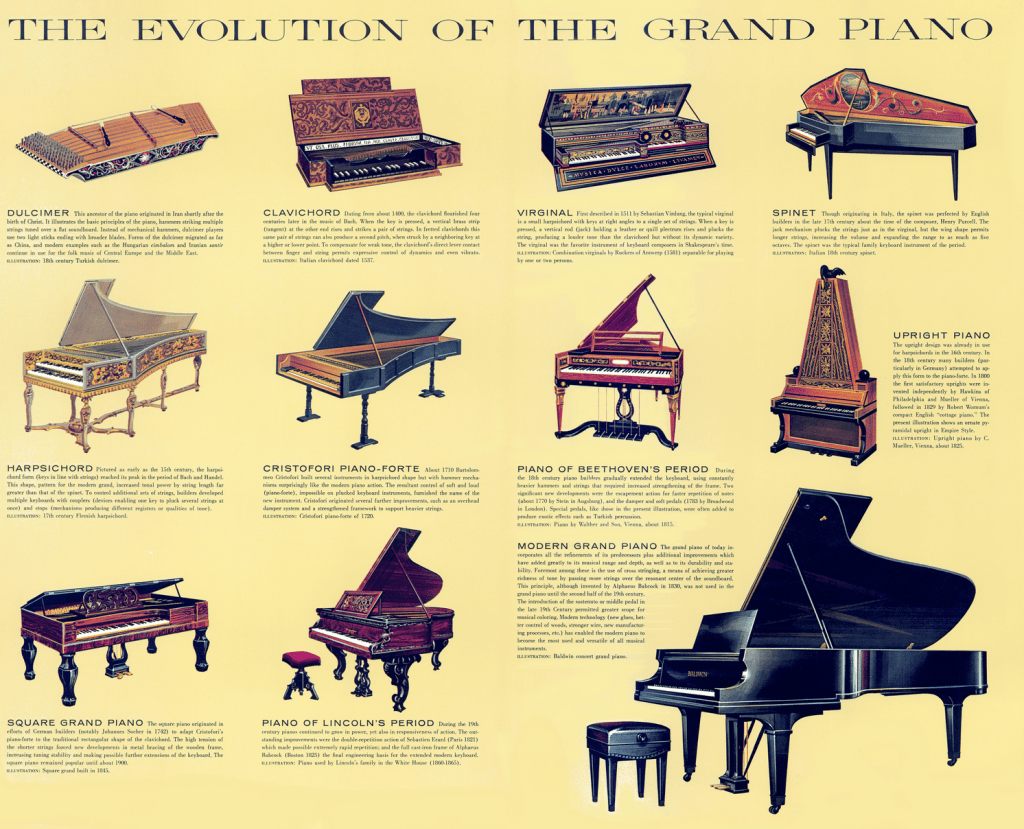

The history of music is a history of technology—and of loudness. “Before the early 19th century, smaller ensembles were the rule. Large concerts were rare, outside of opera, and art music was mostly a private thing, something for the homes of wealthy patrons,” Lolly says. “It didn’t need to be very loud because audiences were small.”

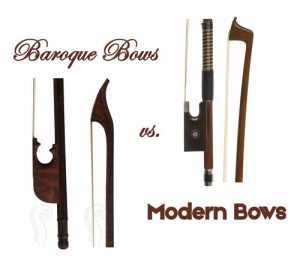

That changed in a big way in the early 19th century, as instrument technology improved. Orchestras were getting larger and wind instruments could freely modulate and stay reliably in tune. Composers began writing virtuosic concertos to be played with the larger orchestras: “The solo artist needed to project over that big ensemble sound,” Lolly explains. Violins, violas, and cellos, the primary solo instruments, had to adapt to handle more string tension. Their bridges were raised to create more resonance; necks were set at a steeper angle; bows were redesigned with a concave curve to allow more tension in the hair.

Baroque and modern violin bows, via Vermont Violins.

“Now we have big, lush string sections and big wind and brass sections with a huge sound,” says Lolly. “That’s what ‘classical’ music sounds like to us—but it’s not how it sounded three centuries ago.”

When she isn’t managing AMN, Lolly is a recording producer. Her interest in early music was sparked in the 1990s when her studio, Transparent Recordings, worked with Bay Area early-music specialists the Artaria Quartet. “It was completely new to me,” she recalls. “I knew it sounded different from modern music, in the intonation and a generally more muted sound, but then I realized that the dynamic range was turned upside down! Instead of emphasizing loudness, there’s a potential for exploring a vast expanse of subtlety that’s almost unlimited. That was really exciting for me.”

Modern instruments aren’t just louder: they’re also able to play reliably in tune in any key. “It all changed with the piano,” Lolly says. “Unlike its ancestor the fortepiano, the modern piano has true ‘equal temperament’—the tuning doesn’t vary across registers and tonal centers. This results in a manufactured tuning system that’s equally out of tune in all keys. Sounds weird, but we’ve become so accustomed to it that this is what our ears are comfortable with now.” Once pianos set the standard, other instruments followed suit.

Professional early-music specialists invest in original or replica instruments—a good bow alone can cost many thousands of dollars. But skilled amateurs can adapt their modern instruments—and their technique—to explore the phrasing and articulation of historical style. The limitations of instruments in the past are now opportunities for discovery for the players of today.

Join us in October to explore some exciting new approaches to familiar and beloved works of music.

NOTE: If you already have Baroque equipment, that’s great! You’ll love working with these great mentors, too.

2 comments

I’d be interested. I only have

a modern instrument and modern but

baroquish bow.

Thanks,

Yvonne Bernklau

510 526-7894

That’s perfect, Yvonne! Do not need any Baroque equipment, just an interest in the syle.