If you’ve spent any time recently on social media—and especially on Twitter, YouTube, or TikTok—you’ve probably found it impossible to escape some haunting, old-fashioned melodies and rhythms. Sometimes sung solo, sometimes in duets, and sometimes in large virtual crowds, these songs have traversed the centuries to become the first earworms of the new year: tunes you just can’t get out of your head.

Welcome to the Great Sea Shanty Craze of 2021: a joyous celebration of tradition, of harmony, and—most of all—of amateur musicianship.

This year’s revival began on December 27, 2020, when a 26-year-old Scottish postman and amateur musician, Nathan Evans, uploaded a video to TikTok, the app for sharing short-form videos. In the video, Evans sings “Soon May the Wellerman Come,” a 19th-century whaling song that originated in New Zealand. (A “Wellerman” was an employee of the Sydney, Australia-based Weller brothers’ shipping company, which between 1833 and 1843 supplied provisions—”sugar and tea and rum”—to whaling ships off the New Zealand coast.)

@nathanevanss The Wellerman. #seashanty #sea #shanty #viral #singing #acoustic #pirate #new #original #fyp #foryou #foryoupage #singer #scottishsinger #scottish

From there, #ShantyTok surged and billowed like a great Pacific wave. There was something oddly timely and—ironically, in this age of COVID—infectious about shanties, with their call-and-response structure that invites participation and their evocation of long voyages to exotic ports. After ten months of pandemic isolation, who among us wouldn’t welcome a trip around Cape Horn or to the South Seas, even if it’s only imaginary?

The centuries-old form has turned out to be a good fit for 21st-century technology. TikTok, for example, allows users to create duets, group videos, and reaction shots that add to the fun.

Only thing I care about now is #shantytok https://t.co/otJYDwD8XN

— Tiffany C. Li (@tiffanycli) January 13, 2021

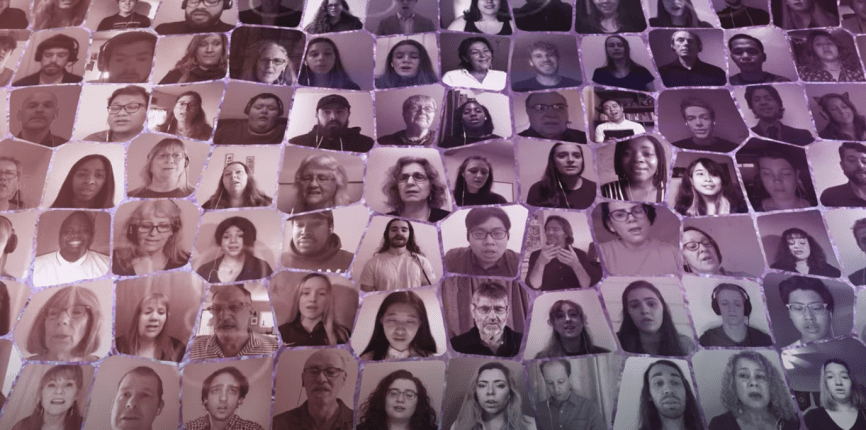

Seas shanties belong to the broad genre known as work songs—songs that either coordinate labor or relieve tedium (or both). Aboard an 18th- or 19th-century merchant-marine ship, a shantyman would lead sailors as they worked; different shanties would accompany different chores. Technically speaking, “Wellerman” is a whaling song, not a shanty, folk musician and music educator David Coffin told the New York Times: “It’s a whaling song with the beat of a shanty, he said, but its purpose is that of a ballad — to tell a story, not to help sailors keep time.” “Leave Her Johnny”—a traditional song first recorded in 1917–is more typical of a true shanty. The Bristol (UK) folk group The Longest Johns recorded it for the 2013 video game “Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag,” which was an early factor in the contemporary shanty revival. In December 2020, The Longest Johns released a new version of the song with hundreds of participants..

“Shanty” is a word with uncertain origins. It’s sometimes spelled “chantey,” which suggests a connection to the French verb chanter, to sing. Spelled “shanty,” it’s unrelated to the “shanty” that refers to a small, rough dwelling; the latter word comes from a French-Canadian source.

If you feel like joining the chorus, the Hyde Street Pier–part of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park–is hosting a live virtual shanty sing at noon on Saturday, January 16. Join the public Facebook group for updates, and watch the video below, filmed before the pandemic, for inspiration. As folk musician David Coffin told the Times, “It’s not the beauty of the song that gets people. It’s the energy. You don’t have to be a trained singer to sing on it. You’re not supposed to sing pretty.”