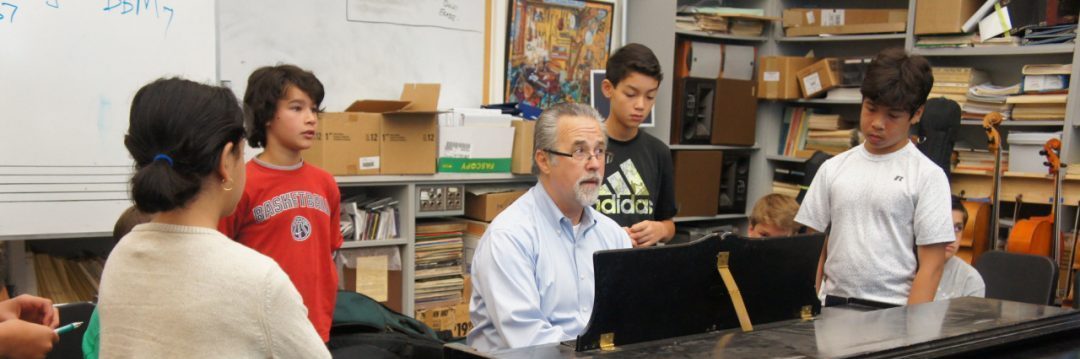

“We all play together” has been pianist, bandleader, and chorus director Bob Athayde’s motto since he began teaching at Stanley Middle School, in Lafayette, California, in 1986. We’ll have a chance to bring that motto to life on March 20, when Bob leads our “Anyone Can Improvise!” online workshop. We reached Bob at his Orinda, California, home to learn more about his career and his approach to teaching.

Tell us a little about your background. Is yours a musical family?

My wife is a musician and music teacher, and all four of my kids play music. I guess they grew up thinking everyone plays music. My son Kyle, who plays trumpet, is my artist-assistant—he’s three times the musician I’ll ever be!

You’ve devoted your professional life to teaching young people. What do you find most satisfying about teaching?

The most satisfying thing is seeing that light bulb switch on in a student’s mind, whether it’s a fourth-grader or an adult. When I can get people to feel joyful about what they’re engaged in I know I’ve gotten the concept across!

You’re teaching remotely now. How is that going?

We closed the school, of course, so I’ve been teaching remotely for a year. But I still go into my classroom, because it makes me feel more businesslike. I have a Steinway grand piano there—it’s in mint condition—plus two computers, an extra camera, and a state-of-the-art microphone with audio interface. I have a big screen and put all the kids’ faces up there.

Do you have any tips for Zoom learning?

I’m used to being in person with large groups of people, so at first, Zoom was strange. After a year of Zooming, I’ve gotten used to it, and am grateful to have that platform. I keep track of teachers around the country who are doing great things with Zoom, and I learn from them.

Besides teaching remotely, what else have you been during during the pandemic, musically and otherwise?

Before Covid, I had a weekly gig playing piano at La Finestra Ristorante in Moraga. That went away, but I now stream a set via Facebook Live every Friday and Saturday from 6 to 7 p.m. I’ve attended a lot of online master classes and listened to [jazz pianist] Herbie Hancock’s Harvard lecture series. And I’ve walked our dog more—and met a lot of neighbors on my walks!

For some classically trained musicians, improvisation can feel a little scary. What can you tell them to make it less daunting?

I’d tell them to be more like kids. To remember that this is your expression—that just as no two people have the same fingerprints, no two people play music the same. You’re making a contribution to art, to music.

Sometimes I look at the piano and tell myself to play something I’ve never played before. Of course I’m filled with ideas of things I’ve done before. But then I might come out with something new and interesting. Listen, I make so many mistakes that if I were leading a band I probably wouldn’t hire me! But I don’t care, because I’m batting .500, which would get me into the major leagues.

And remember: it’s playing music, not working music!

Photo of Bob with students: Kerwin Lee