What does it take to collaborate musically? How do you find a musical collaborator who’s right for you?

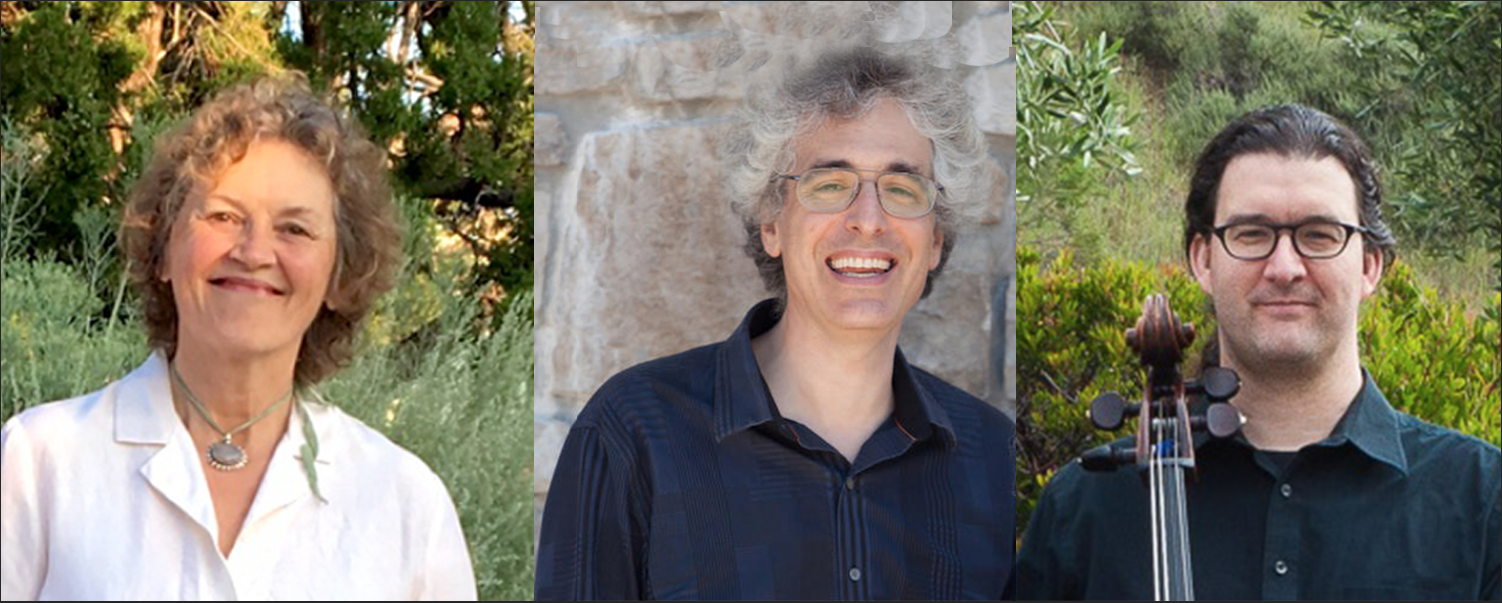

In anticipation of our September 26 online conversation about collaboration with pianist Gwendolyn Mok, we chatted with Robert Howard, who will moderate the conversation. Robert is an accomplished cellist who has collaborated with Gwen and other pianists in performance and on recording; during the workshop, he and Gwen will play excerpts from Beethoven’s Cello Sonata in g-minor and Rachmaninoff’s Sonata in g-minor for Cello and Piano.

What’s the difference between an accompanist and a collaborator?

I think of a collaborator as an equal partner—someone who will make things interesting without drowning out the other performer.

Occasionally with some virtuoso repertoire you want an accompanist who’ll stay in the background. But for the workshop Gwen and I deliberately picked pieces that have some involved piano parts, so Gwen can have an opportunity to shine.

How do you find the right collaborator?

The best way is through a trusted musical acquaintance—sort of a matchmaker—who will make an introduction. Or you might find someone through a chamber-music workshop, a reading session, or a house party. Speaking for myself, I have to hear the person play. I can usually tell within a few lines if there’s potential there.

How have you and Gwen prepared for the September 26 workshop?

Gwen and I have played together previously—last year I was one of five cellists who played the five Beethoven cello sonatas with her. Because of the pandemic, we’ve prepared mostly by talking on the phone and having a Zoom cocktail hour. But we finally got together to rehearse in the same room on September 16, at her house in Berkeley. We’ll do the online workshop from my house in San Francisco. In both places there’s plenty of room to be safely distanced!

You normally have an intense performance schedule. Obviously, that hasn’t been happening because of COVID. How have you been keeping busy and engaged?

There have been a few silver linings, one of them being how everything’s so international now. I’ve been taking lessons from a very fine cellist in Berlin, and I’ve been teaching students in Kenya and Colombia.

And I’ve appreciated all the creative content on Instagram. YoYo Ma posts something almost every day—speaking of great collaborations, he’s played via Zoom with a singer in Mali, some musicians in China, the Syrian clarinetist Kinan Azmeh, and many other people. Pablo Ferrández is an excellent Spanish cellist with a very active Instagram account. And Nathan Chan, who’s a Bay Area native and the youngest member of the Seattle Symphony, recently posted a video of his performance of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” before a San Francisco Giants game at T-Mobile Park!

_

Follow Robert on Instagram at @rhowardcello.

Learn more about Gwendolyn Mok on her website.

.

We hope you’ve registered for our

We hope you’ve registered for our